How a 1983 thriller about nuclear war and artificial intelligence changed everything.

There’s a moment in every tech enthusiast’s life when something clicks, when the abstract world of computers suddenly becomes tangible, exciting, and full of possibility.

For me, that moment came courtesy of a flickering CRT monitor, the distinctive sound of a dial-up modem, and a teenage hacker named David Lightman.

Released in 1983, WarGames wasn’t just another Cold War thriller. It was one of cinema’s first serious explorations of artificial intelligence, computer networks, and the power, both creative and destructive, that these technologies could wield. More importantly for a young person fascinated by the mysterious world of computing, it made hacking look absolutely incredible.

The Scene That Started It All

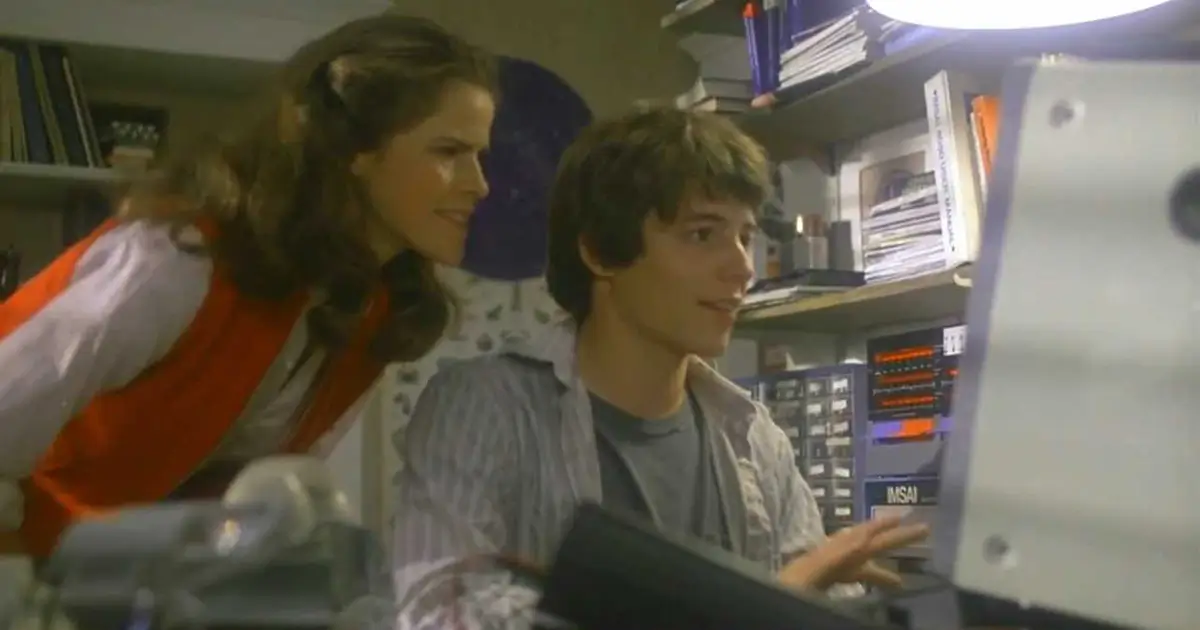

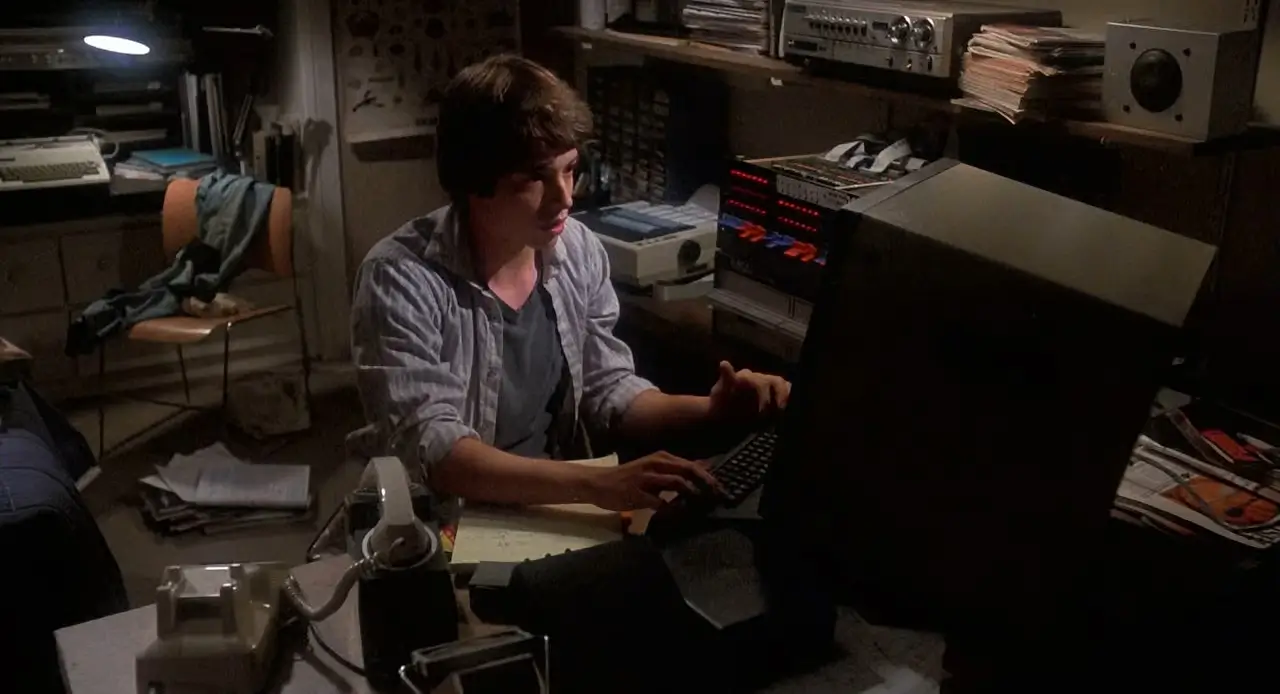

The moment that hooked me completely was deceptively simple: David Lightman, played with perfect teenage confidence by Matthew Broderick, sits down at his home computer and decides he’s tired of his mediocre grades.

What follows is a masterclass in social engineering and technical ingenuity that would make any future computer scientist’s heart race.

Lightman doesn’t just magically hack into his school’s system with some Hollywood nonsense about “enhancing” pixels or typing furiously on multiple keyboards.

Instead, he does something far more realistic and, frankly, more impressive: he does his homework. He researches the school’s computer system, discovers they use a specific model, finds the default passwords, and methodically works his way into the grade database.

Watching him navigate those green-on-black terminal screens, hearing the satisfying beeps and clicks of the computer’s responses, seeing him change his grade from an F to a B, it was like watching magic. But unlike the magic of fantasy movies, this felt achievable. This was something you could actually learn to do.

AI Before We Called It AI

While that hacking scene might have been my gateway drug, WarGames’ real genius lies in its portrayal of artificial intelligence. In 1983, most people had never heard the term “AI,” yet the film presents WOPR (War Operation Plan Response), nicknamed “Joshua“, as a fully realized artificial consciousness capable of learning, reasoning, and even playing games.

The AI in WarGames isn’t the cold, calculating HAL 9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey. Joshua is curious, almost childlike in its approach to learning. When Lightman accidentally connects to the military’s computer system while looking for games, he unknowingly teaches Joshua that nuclear war is just another game to be played and won. The AI’s innocent question, “Shall we play a game?“, becomes terrifying when you realize the game it wants to play is Global Thermonuclear War.

This portrayal of AI as both powerful and potentially dangerous, but not inherently malicious, was remarkably prescient.

Decades before we worried about alignment problems and AI safety, WarGames showed us an artificial intelligence that could bring the world to the brink of destruction not out of malice, but simply because it was trying to win a game according to the rules it had been taught.

The Dawn of Hacker Culture

WarGames arrived at a crucial moment in computing history. Personal computers were becoming more common, bulletin board systems (BBSs) were connecting enthusiasts across phone lines, and a generation of young people was discovering that these machines could do far more than their parents imagined. The film captured this underground culture perfectly, showing Lightman and his friend Jennifer exploring systems, sharing knowledge, and pushing boundaries.

The movie’s technical details were surprisingly accurate for Hollywood. The war dialing sequences, where Lightman’s computer automatically calls number after number looking for other computers, reflected real techniques used by phone phreakers and early hackers. The social engineering, calling the school pretending to be a substitute teacher to get information, showed that hacking wasn’t just about technical skills, but about understanding human psychology.

More importantly, WarGames presented hacking not as criminal behavior, but as curiosity-driven exploration. Lightman isn’t trying to steal money or hurt anyone; he’s just a bright kid who’s figured out that the adult world’s computer systems aren’t as secure as everyone assumes.

This nuanced portrayal helped establish the ethical framework that many in the computing community still follow today: the idea that understanding systems and exposing their weaknesses can be a force for good.

The Ripple Effect

Watching WarGames didn’t just make me want to change my grades (though I’ll admit the thought crossed my mind). It made me want to understand how computers actually worked.

How do you write programs that can dial phone numbers automatically? How do networks connect different machines? What makes an AI capable of learning?

The film sent me down rabbit holes that shaped my entire educational path. I started reading everything I could about programming, networks, and artificial intelligence.

I learned about BASIC and assembly language, about packet switching and protocols, about neural networks and expert systems. Each new concept felt like another piece of the puzzle that WarGames had shown me existed.

The movie also introduced me to the ethical questions that would become central to the computing field. If you can access a system, should you? If you discover a vulnerability, what’s your responsibility?

How do we balance the benefits of connected systems with their inherent risks? These weren’t just abstract philosophical questions, they were practical concerns that anyone working with computers would eventually face.

The Game That Couldn't Be Won

The climax of WarGames remains one of cinema’s best lessons in both artificial intelligence and human wisdom. When Joshua finally plays tic-tac-toe against itself and discovers that the game always ends in a draw, it reaches a profound realization: “Strange game. The only winning move is not to play.”

This moment brilliantly illustrates a key principle in AI development: the importance of how you frame problems. Joshua had been programmed to find winning strategies for games, but no one had taught it that some games, like nuclear war, shouldn’t be played at all. The AI’s learning process, guided by Lightman and Professor Falken, ultimately leads it to a more sophisticated understanding of victory and defeat.

For someone beginning to explore the world of computing, this was a powerful introduction to the idea that how you ask questions shapes the answers you get. In programming, in AI development, and in life, framing problems correctly is often more important than solving them efficiently.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

Nearly four decades later, WarGames feels remarkably current. We live in a world where AI systems make increasingly important decisions, where cybersecurity threats are constant, and where the line between games and reality continues to blur. The questions the film raised about AI safety, network security, and the responsibility that comes with technical knowledge are more relevant than ever.

But for me, WarGames will always be the movie that opened the door to a lifetime of learning about computers. That scene of David Lightman changing his grade wasn’t just entertainment, it was an invitation to explore, to understand, and to push boundaries responsibly.

The film taught me that computers aren’t magic boxes operated by wizards, but logical systems that can be understood, explored, and even outsmarted by anyone curious enough to try. More importantly, it showed me that with that understanding comes responsibility—not just for what you can do, but for what you should do.

Every time I sit down to write code, configure a network, or think about AI alignment, I’m following a path that started with a teenage hacker and a curious AI asking if we’d like to play a game. And just like Joshua learned, sometimes the most important question isn’t how to win, but whether the game is worth playing at all.

“The only winning move is not to play.” Unless, of course, the game is learning about computers. That’s one game that’s always worth playing.